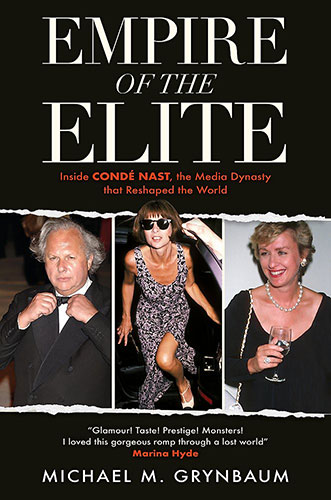

If you love gossip, glossy mags and tales from a different era of New York, you’ll love the new book Empire of the Elite: Inside Condé Nast, the Media Dynasty That Reshaped America.

Written by New York Times reporter Michael M. Grynbaum, the hefty but entertaining tome offers a history of the famous – and famously flashy – publishing house behind the likes of Vogue, Vanity Fair and The New Yorker, exploring the legacy and influence of owner Si Newhouse Jr, long-standing editorial and art director Alex Liberman and famous editors Anna Wintour, Graydon Carter, Tina Brown and more.

In this extract, Grynbaum writes about the excess and ‘what budget?’ attitudes of a very different time in media.

If you made it at Condé Nast, you reaped the spoils. The mandate to live expensively had deep roots in the company’s DNA. In 1928, when Edna Woolman Chase was planning to build a country home on Long Island, Condé Montrose Nast offered her a gift of $100,000 – $1.8 million in today’s dollars – for its construction.

Edward Steichen, the pioneering fashion photographer, received a $35,000 contract to shoot for Vogue and Vanity Fair in 1923 – $625,000 in today’s dollars. Alex Liberman believed deeply in this tradition. For decades, he served as the in-house philosopher of excess, defending the company’s decadent spending as the necessary price of achieving artistic excellence. Alex was a proselytiser of waste – creative waste. It cost money to generate the avant-garde design, iconic photographs, and ambitiously reported journalism that distinguished Condé Nast from its competitors, to reach the heights that Alex believed were necessary for the company to be, as he put it, “one of the great civilizing forces in America.”

Thanks to Alex’s ideas and Si’s largesse, Condé culture boiled down to a simple dictate: it was always better to spend than not to spend. Editors were encouraged to toss away photo shoots and kill expensive articles. When Vogue commissioned Irving Penn to photograph a broken Champagne glass, Alex insisted that the magazine smash a hundred samples from Cartier in order to procure the perfect image.

“We were always given this idea that you had to aim for some sort of artistic perfection,” said the photographer Sheila Metzner, another Liberman protégée. “Your references were the greatest movies, or the greatest books, or the greatest artists – and whatever you had done before, you had to do better than that.”

This was the mandate that allowed Diana Vreeland, in the 1960s, to spend tens of thousands of dollars insisting that Richard Avedon twice reshoot a fashion spread on the color green. Vreeland wanted the hue to resemble the baize of a billiards table, and upon reviewing Avedon’s contact sheets, she was convinced the photographer hadn’t gotten the color quite right. Finally, fed up, Avedon tore off a strip of felt from an actual pool table and presented it to Vreeland’s office. See? he demanded. It’s the right hue.

“Oh,” Vreeland said, distractedly. “But I meant a billiard table in the late afternoon sunlight!”

Vreeland once flew David Bailey to India for a shoot involving white tigers that never ran. Recalling that the British photographer Norman Parkinson had glimpsed fields with white horses on a trip to Tahiti, she enlisted him to return to the island, “select the finest Arab stallion,” and drape the animal in mounds of silver and gold fabric. Upon arrival, Parkinson was told that all of the white horses had been eaten by French colonisers. When a (brown) stallion was finally located, and weighed down with 150 pounds of fabric, the horse got spooked and leaped into the air, sending the fabric flying. A pony had to be used instead.

When Polly Mellen came over from Harper’s Bazaar in 1966, her first assignment was “The Great Fur Caravan,” a five-week-long, first-class tour of Japan with Avedon and the model Veruschka, accompanied by enormous trunks of winter clothing carried by a crew of local laborers.

“Money,” Mellen told me fifty-six years later, “was not something that was given a thought.”

The grand only got grander when Si Newhouse took full control of his father’s company, and Condé’s revenues and relevance began to swell. Alex, who saw no distinction between creative pursuit and financial comfort, believed that the propagators of Condé’s luxurious dreamland ought to live inside the lives they conjured on the page. “I believe that money should be used to facilitate a creative life and to eliminate fatigue,” he said. “I take taxis all the time; I find them restful and stimulating.”

Shortly after Grace Mirabella assumed the editorship of Vogue in the early 1970s, Alex called her to his office at 350 Madison and offered some advice on an upcoming shoot she was overseeing in Paris. “Take the Concorde,” Alex instructed. “Spend a lot of money. Get yourself there in the most expensive way possible, take pictures over ten times if you need to. Do it all grandly!”

• Empire of the Elite: Inside Condé Nast, the Media Dynasty That Reshaped America by Michael M. Grynbaum (published by Hachette) is out now, $40

.jpg)