When Ensemble talked to director, producer and overall filmmaker extraordinaire Chelsea Winstanley exactly five years ago, she was embarking directing on her first feature documentary project, TOITŪ: Visual Sovereignty, following the largest ever exhibition of contemporary Māori art, curated by Nigel Borell for Toi o Tamaki Auckland Art Gallery.

Five years on, and the film has premiered at the New Zealand Film Festival to a unanimously warm response. Winstanley has also moved from the edge of the spotlight, a facilitator and enabler of other people’s art, to being the headliner.

In addition to that, there is now an ONZM attached to the end of her name, she has shepherded five te reo translations of Disney films following the success of the Moana translation through Matewa Media and she currently serves as the co-chair of the board of the Arts Foundation Te Tumu Toi.

So, it’s been a big five years.

The big project in the spotlight at the moment is TOITŪ: Visual Sovereignty. Even though the documentary started filming in 2020 – amidst pandemics and lockdowns – Winstanley first heard about the exhibition in 2018.

“I’d come home from LA for a quick visit”, she recalls. “I’d caught up with Nigel Borell who was a curator at the gallery at the time. It sounded incredible, a takeover of the gallery curated by Māori, and it was going to be as big as Te Māori [previously the largest exhibition of Māori art, that toured internationally in the mid-80s].”

“It felt like this massive turning of the tide perhaps, within our organisations, our institutions. I thought, ‘Wow, this is going to be incredible.’”

Winstanley kept talking to Borrell, and was adamant that the process of curating the exhibition should be documented, as it was monumental. A subsequent conversation with then gallery director Kirsten Lacy was had, and she was given the metaphorical keys to the kingdom to film the process.

“As a member of the public, we get to view these pretty things on the wall and get all the yummy end parts but we don’t really know what goes on behind the scenes, how many people are working on it, how do you pull this together and curate it,” she says.

“I was really interested in Nigel’s thoughts around that.”

Things didn’t go to plan however. By the time Winstanley was ready to come home to start filming, the pandemic had struck, and she was locked down in Los Angeles. She describes it as a time of “crazy turmoil” (relatable). She thought, “‘Get me the hell out of here. I’m coming home.”

She hit the ground running as soon as she got out of quarantine. A decision was made that the film would be done independently, to free them from the restrictions and timeframes that are the unfortunate strings attached when it comes to a funded film. “I thought it was such an important thing to do that I was gonna do it no matter what.”

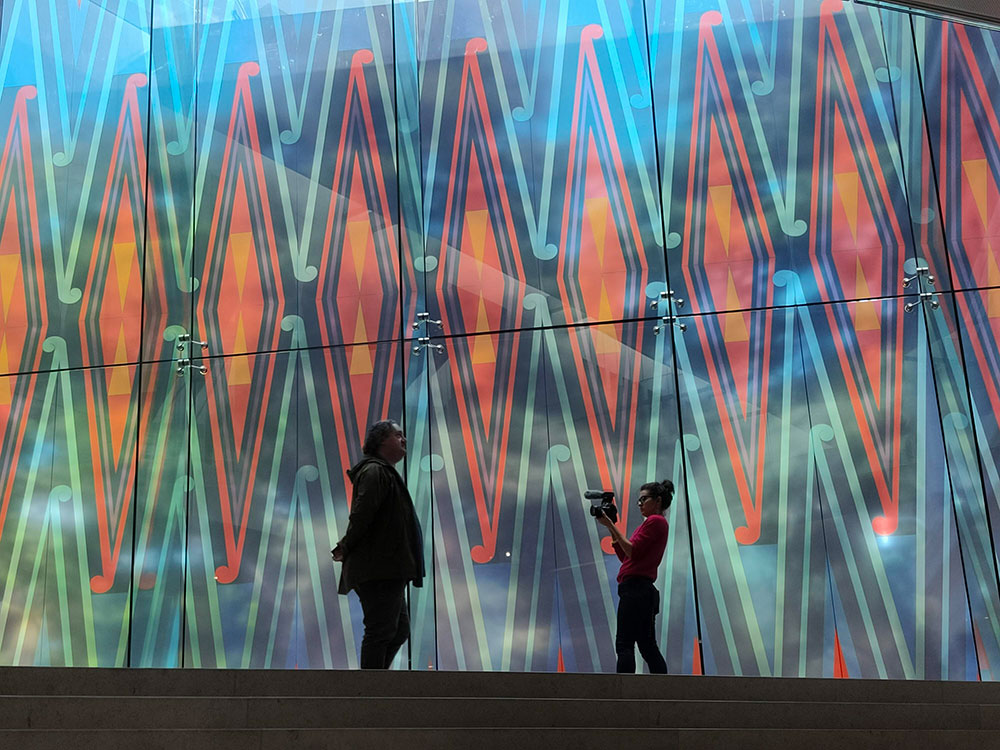

The most remarkable thing about TOITŪ isn’t necessarily some of the drama at the centre of the film – Borrell’s relationship with an institution that seems to prefer Māori input over Maori leadership, and that same institution’s desire to frame artists out rather than frame them in – but the remarkable amount of access that Winstanley gains with the artists who were part of the exhibition, including the likes of Mataaho Collective, Shane Cotton, Reuben Paterson, amongst many others.

“Maybe it’s that intrinsic thing about that te ao Māori perspective – whanau, hapu, iwi – we’re all entwined with whakapapa,” she says. She points back to one of her first gigs: working behind the scenes on Māori Television’s Kete Aronui, which followed leading Māori contemporary artists. Somehow she ended up watching an episode with sculptor Freddie Graham, while his granddaughter was babysitting her kids.

“It’s a matter of trust – building that trust - and being gentle,” she says. That extends to the style of the film – it’s extremely unobtrusive and the artists speak for themselves rather than being led to predetermined conclusions. “Just don’t get in their way, and document what they’re up to. That’s good for the artists too, because they probably never really have people following their process. They’re always doing.”

Another important part of Winstanley’s recent mahi – that so happens to have a little bit of philosophical overlap with TOITŪ – is serving as the co-chair of the Arts Foundation Te Tumu Toi. For many, the purpose of the Foundation might seem obvious on the surface: they give artists money annually, in the form of several awards. Most notably, these are the Laureate Awards, which are handed out at a glamorous ceremony annually, but they also award Springboard Awards to emerging artists, and Icon Awards to, well, icons.

The real function of it is something much more important. It’s a crucial pillar of the arts sector, one of the few genuine bridges between philanthropy and creativity. Winstanley’s role as co-chair is a relatively new one for the organisation, December will mark her third year in the role. She puts it simply: “We work really hard to recognise and share the power, build the bridge.”

In this role, Winstanley has the enviable job of getting to call the award recipients to tell them they’ve won – and that they’ve been chosen to receive an award by their peers who recognise them, see them as an artist and want them to get the support they deserve. “People cry, it’s so amazing. It’s just beautiful, because half the time, they might be going, ‘Oh my god I was about to give up!’ or ‘I didn’t know people really saw me’. It’s beautiful.”

In that interview with Stacey Morrison for Ensemble five years ago, Winstanley shared that returning to directing meant embracing the creativity she hasn’t always been able express as a producer. “I hadn’t had any aspirations of being a producer, in all honesty,” she says. “When I went to uni and studied, I didn’t really know what producing was actually. I did the AUT communications degree because I knew at the end of the third year, if you majored in television, you got to make a little documentary. That was all I had in my mind, that was all I was going for.”

When she finished and started working with Kiwa Productions, she nurtured the producing seed, and she’s grateful for the learning that she experienced in that time. “Maybe it makes me a certain type of director because I know how important producing is – I know limitations, how to work with whatever you’ve got, and how to get a project onscreen.

“If you’re going to make something on your own, it’s good to have those skills too. I think for me, it’s really solidified that this is the direction I want to take the rest of my career in.

“I’m almost 50, so I better bloody do it!”

Screenings as part of NZIFF are selling fast - Auckland sessions are sold out, but an encore Wellington session has just been announced. Tickets are also still available for Christchurch and Dunedin sessions. With such strong interest, plans are underway for special screenings beyond the festival. You can find out about screenings and request a viewing at thistooshallpass.nz/toitu or check Instagram @toituvisualsovereignty

.jpg)