It launched 20 years ago in September, and a single spritz is all it takes to wrench me back. I’m 17, lodged in the rhythms of suburban adolescence, with blonde hair and baby tees, all of it awash with the syrupy notes of Fantasy eau de parfum.

I can smell it a mile away, even now, imprinted in my psyche alongside The OC, Swing by Savage and those stretchy belts from Supré that would go some way to covering the soft expanse of pelvis revealed to the world by your low-rise jeans. It’s lodged in the vault with Lancôme Juicy Tubes, pink Chucks and Nokia 3310s, and everything with even slightly permeable material qualities smelled like Fantasy; my red Mazda Astina, Roxy bikinis, and Dickies.

Britney Spears' second perfume, it had the might of Elizabeth Arden behind it. Curious was first, in 2004, and a success too. But Fantasy, an Ann Gottlieb creation released the following year, was the true essence of Britney, distilling it into notes of fertile fruit lychee, quince, kiwifruit, cupcake, wild chocolate orchid and musk.

Categorised as a gourmand scent, though they’re common now, Thierry Mugler Angel was rather radical when it came out in 1992, and it’s understood wisdom that their appeal lies in their sugary simplicity. These perfumes are palatable – bestowing that same quality on the girl wearing them – and acceptable, often considered an age-appropriate first perfume, since young women should smell like fruit (ripe, fertile) or candy (dopamine-spiking sweetness).

And we wanted to. Sales of Fantasy grossed more than US$30 million in the first three weeks.

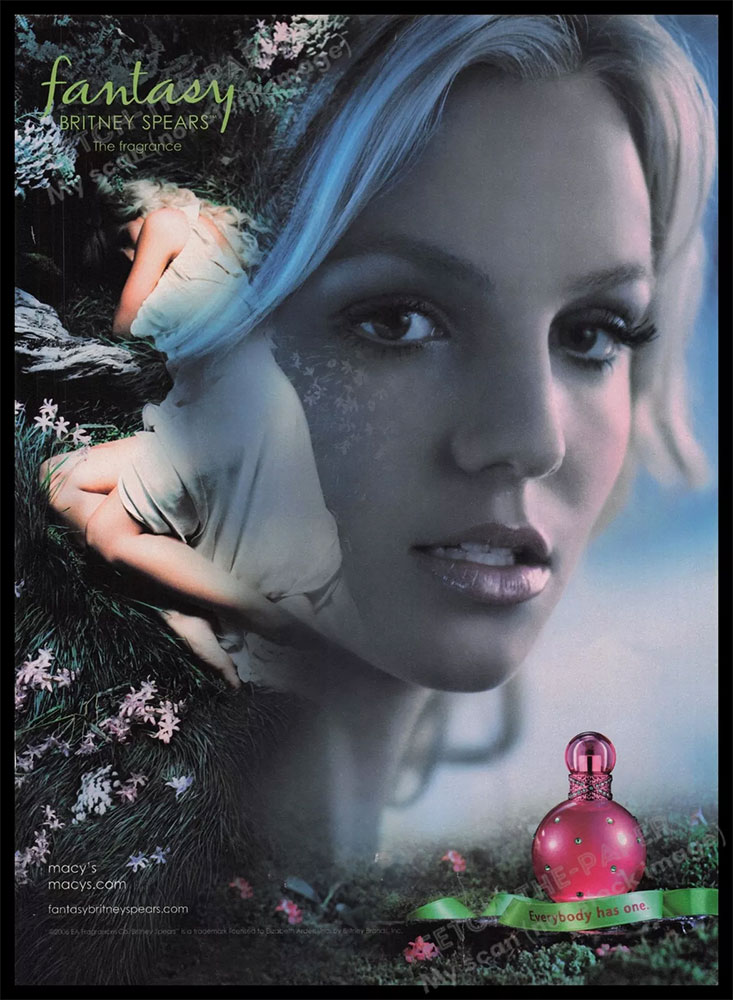

The nubile round bottle (designed by Jean Antretter) was made from pink glass, and because it was sophisticated, it was studded with Swarovski crystals. It came packaged in a swirly Pucci-esque print and opened like a museum display box. (Podcast Nymphet Alumni dubbed this “saccharine, age-regressive genus of commodity fetishism” Sugar Cookie Consumerism and their analysis of the bigger picture is great). Youth felt like it was up for grabs back then, and certain accords of girlhood were ripe for the plucking.

Fantasy was, in my personal history, preceded by the sweet, shimmery Baby Doll by Yves Saint Laurent, Clinique Happy, and the sleek and edgy CK One by Calvin Klein. It was at the fragrance counters of the mall that we would experience them all first, on those little paper cards and our growing wrists.

In suburban Auckland of the early 2000s, shopping centres were places of self-discovery, territory to decide which edition of girlhood we wanted to be – should be – as we shrugged the iconography of womanhood on and off, looking for one that fit. Safe, more or less, under the watchful eye of CCTV and security guards, teenage girls explored a fantasy of independence.

And, armed with bus fare and some pocket change, newfound spending power, indulging in commodities designed for our disposable incomes: Bright, flimsy tops – dopamine dressing before we called it that – accessorised with cheap earrings, Starbucks and lipgloss. The beauty section and its bounty within were generally reserved for when you were “old enough”, and fragrances were, as such, a ritualised rite of passage. (Viktor & Rolf’s Flowerbomb came out the same year as Fantasy, and you could find that at another site of pilgrimage: Karen Walker’s Newmarket boutique).

Performing and practising, we mirrored what we saw in the pop culture panopticon, all eyes and cameras trained on the latest crop of celebrity, with their long hair, low waistbands and glossy lips, pupils haloed by music video eyelights. Christina Aguilera, Destiny’s Child and Rihanna. That vision of femininity was intoxicating, and fragrances were designed accordingly.

Jennifer Lopez, Paris Hilton, Jessica Simpson and Gwen Stefani all had their own scents. By 2010, Beyoncé and Taylor Swift had both joined them. The fame formula had unlocked a younger consumer and the category boomed (all were produced by big beauty corporations like Coty, Estée Lauder and Elizabeth Arden). Atop them all was Britney. The original, the template and, for my generation, the first of all the blondes that followed.

In 1998 ...Baby One More Time changed pop culture and the fantasy of Britney Spears was born. There she was on the cover of Rolling Stone, both innocent and sexy, in her teenage bedroom in that controversial shoot by David LaChapelle. (The story behind the editorial, and whose idea it was for the 17-year-old to undress, is worth revisiting; a couple of years later the photographer and his subjects, teenage heiresses Paris and Nicky Hilton, would take a similar rogue approach to a Vanity Fair shoot.) It was the first of many covers for Britney, her image and message evolving with each one.

The powerful image-making mechanics at work in her career and the media of the time saw her lensed by some of the best; Herb Ritts for the 2001 cover of US Vogue, Peter Lindbergh for Kenzo, and Annie Leibovitz for a Candie’s footwear campaign. Ellen von Unwerth – she of Claudia Schiffer’s Guess campaign, Naomi Campbell and Kate Moss in the bath, and Hole’s Live Through This album cover – shot the print campaign for Fantasy.

The fragrance was, media coverage explained, representative of a new era for Britney (married, womanly), a message contradicted by its girlishness. Another paradox was the critical acclaim it enjoyed alongside mass appeal, a kind of high-low duality that’s easier to swallow now. Within their symbiotic dynamic, Britney and Elizabeth Arden built a hugely lucrative perfume empire.

It all looked like a success story – giving the world album after album, fragrances, and giving birth to two sons – but that was a kind of fantasy too. Its shattering was more like a slow fracking: cracks, bubbles, seepage. Her very clear, very public chafing against the situation she found herself in was a frequency that young women feel and recognise. The volume increased, and we all know what happened next, though recent cultural reappraisal has turned the house lights on the darkness of the time. Pandora Sykes’ podcast Pieces of Britney is one of the better records of this period, part of a wider revisionist lens on the media canon around her, and the infrastructure of her career.

Even now the general perception of Britney is one of fragility. Though she’s understood to have regained agency, there’s a voyeurism inherent to following her on Instagram and reading all the news stories, and a veil up. The truth, the real Britney, is unknowable; she remains a fantasy.

Writing this, I revisited the original campaign. In the print advertisement we see two Britneys. One, her famous face in close-up, looking over her shoulder to eyeball Ellen’s camera. The other (in birds-eye view) is curled in fetal position on the grass, face hidden, and the sense of vulnerability and voyeurism is uncomfortable with the benefit of hindsight. The television commercial cast her as a goddess being chased by a bow-wielding hunter. That feels unsettling now too.

You can still buy it, that bottled essence of Britney, and a 100ml bottle will set you back about $40 (she earns millions from her fragrances each year). Two decades on from that first Fantasy, Elizabeth Arden continues to release new editions; the latest, “Candied Fantasy”, hit the market last year. It promises to “make life a little sweeter”.